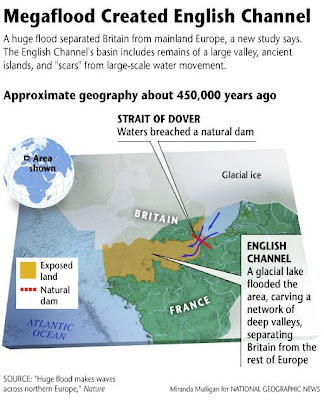

A flood of biblical proportions cut the British Isles off from mainland Europe sometime between 450,000 and 200,000 years ago, according to a new study. The research, based on three-dimensional sonar mapping of the English Channel, provides the strongest evidence yet that a catastrophic megaflood broke a land bridge that once connected what is now Britain and France.

"It is probably one of the largest floods ever identified," said Phillip Gibbard, a geographer at the University of Cambridge who wasn't involved in the study.

At its peak, the flood would have discharged water at a rate of about 264 million gallons (a million cubic meters) a second, gushing at speeds of up to 62 miles (100 kilometers) an hour, the researchers say. This is roughly equivalent to ten times the combined flow rate of all the rivers in the world.

In addition to making Britain an island, the authors add, the huge flood had wide-ranging environmental consequences.

For example, the gigantic pulse of freshwater entering the Atlantic Ocean likely caused a period of climate cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, Gibbard said.

"The introduction of ice and freshwater into an ocean drives climate oscillations and causes marked cooling events," he explained.

The flood also marooned many animals and plants, so those species gradually evolved into different forms than their mainland cousins.

And humans appear to have avoided the newly made island altogether, leaving it unoccupied for over a hundred thousand years.

Crumbled Chalk

Researchers have long known that a narrow ridge of chalk once connected Dover in southeast England to Calais in northwest France (see a map of France showing Calais' proximity to Britain).

During the ice ages, when sea levels were low, the ridge held back a glacial lake from inundating a large valley between the two regions.

But during warm interglacial periods, sea levels rose and the chalk ridge was the only link. At some point the ridge crumbled. Theories as to why have included river or glacial erosion, tidal scraping, and—most controversial of all—a megaflood.

Now Sanjeev Gupta of Imperial College London and colleagues say they have found the first concrete evidence to support the megaflood theory.

A 3-D map of part of the English Channel reveals features that could only have been created by a massive flood, the team says.

"We have identified huge scours on the seafloor and streamlined islands," said Gupta, whose results will appear in tomorrow's issue of the journal Nature.

These features are very unusual, he said, and have previously been found only in regions where megafloods are known to have occurred.

Similar features exist, for example, in the Channeled Scabland in eastern Washington State, which was deluged when the glacial Lake Missoula burst its banks about 12,000 years ago.

Isolated Island

Based on their analysis, Gupta and colleagues say the most likely source of all this water was a huge glacial lake sitting in what is now the southern North Sea off the east coast of Britain.

The water was probably held back by the chalk ridge, and a small earthquake could have caused the first few cracks to appear.

"Chalk is not very strong, and eventually the water probably just started to over-spill," Gupta said.

Determining exactly when the megaflood took place is difficult.

But the divergence of plant and animal species between Britain and mainland Europe suggest that the event must have occurred sometime between 450,000 and 200,000 years ago.

"We now need to drill into the sediments to get an accurate date," Gupta said.

The great flood could help explain why Britain remained an uninhabited region for a large chunk of the archaeological record.

"There seems to be a large gap in the evidence for human occupation [of Britain] during cold and warm phases from about 180,000 until about 60,000 years ago," said Nicholas Ashton, an archaeologist at the British Museum in London.

(Related: "Humans Sped to U.K. After Ice Age, Study Says" [November 3, 2003].)

When the climate was warm, sea level between the island and the mainland was too high for humans to cross, Ashton said.

And during the much colder ice ages, humans could have crossed, but seem to have preferred to live in sunnier regions such as modern-day Italy and Spain.

"It wasn't until 60,000 years ago," Ashton said, "that humans—late Neanderthals—had the technological capabilities, such as more effective clothing and shelter, to survive the cold conditions."

National Geographic NewsRare "Octosquid" Captured in Hawaii

Alien Life May Be "Weirder" Than Scientists Think, Report Says

National Geographic

No comments:

Post a Comment